Cheatsheet - Crypto 101

Category: cheatsheetTags:

Crypto 101

This is a beginner guide, not an Academic paper

Also this is very summary and CTF-specific. If you are interested in Crypto check out crypto101.io

This Cheatsheet will be updated regularly

When you are trying to solve a Crypto Challenge for a CTF, first of all, you need to detect which Cipher is used.

For example if it’s a Symmetric or Asymmetric cipher, a Classic cipher or if it’s just an Hash.

Keep in mind that CTFs are meant to be broken so think before implementing a bruteforce over an AES-128 key.

Bruteforce may be present but only over a limited key-space or time-span

NOTE: Most of the time the encrypted message is the flag, and most of the time the flag is in a known format like ctfname{data} so this will leak part of the plaintext. Be smart

Misc

If your ciphertext has lots of numbers and @\>%, don’t worry it’s rot47

If your ciphertext has only uppercase letters and numbers test it as base32

If your ciphertext has alphanumeric chars and ends with = or == it’s base64

It might be that they used their own alphabet for the base64. Check this page to better understand this.

Always test for rot13 if the challenge gives only few points.

Hash

There are some tool to detect the hash type (if it’s not known), but a search on DuckDuckGo with the prefix hash will also do the trick.

If organizers are using a custom hashing algo you won’t find it, but I hope you will find out it’s custom (and broken).

Now that you know what hashing algo it is, most of the time you will need to find some sort of collision.

Collision

If it’s a (not-full) prefix/postfix/pattern collision, you can solve it by bruteforce.

Sometimes this falls under the term PoW (Proof-of-Work).

e.g. Calculate a string str such that sha1('SaltyToast'+str) start with '00000'

See this python script that solve the example above

Merkle-Damgård based hash functions

Merkle-Damgård based hash functions (MD5, SHA1, SHA2) uses this construction:

Reusable hash collision

Let a and a’ be strings with length(a) = length(a’) = multiple of input block length,

Let H0 be the hash function without length padding

Let || be the concatenation function

H0(a) = H0(a’) implies H(a || b) = H(a’ || b) for an arbitrary string b

Then the pair a/a’ is a reusable hash collision

In this case if there is a public known existing collision, you can append the same message to get another collision.

e.g. With this Python script

import md5

m = md5.new()

m1 = '0e306561559aa787d00bc6f70bbdfe3404cf03659e704f8534c00ffb659c4c8740cc942feb2da115a3f4155cbb8607497386656d7d1f34a42059d78f5a8dd1ef'.decode('hex')

m2 = '0e306561559aa787d00bc6f70bbdfe3404cf03659e744f8534c00ffb659c4c8740cc942feb2da115a3f415dcbb8607497386656d7d1f34a42059d78f5a8dd1ef'.decode('hex')

a = 'Hello World'

mm1 = md5.new()

mm2 = md5.new()

mm1.update(m1)

mm2.update(m2)

assert(mm1.digest() == mm2.digest())

mm1.update(a)

mm2.update(a)

assert(mm1.digest() == mm2.digest())See this SharifCTF 7 Challenge

Length Extension

Given the hash H(X) of an unknown input X, it is easy to find the value of H(pad(X) || Y), where pad is the padding function of the hash. That is, it is possible to find hashes of inputs related to X even though X remains unknown.

A great tool for performing automatic Length Extension attack is HashPump.

Alternatively if the challenge is using a custom hash or if you want to implement your own length ext. attack you can follow this writeup from team spritzer.

I will report and decribe here their code for the extend function:

NOTE: SLHA1 is a custom hashing algorithm derived from SHA1

def extend(digest, length, ext):

pad = '\xfd'

pad += '\xab' * ((56 - (length + 1) % 64) % 64)

pad += struct.pack('>Q', length * 8)

slha = SLHA1()

slha._h = [struct.unpack('>I', digest[i*4:i*4+4])[0] for i in range(6)]

slha._message_byte_length = length + len(pad)

slha.update(ext)

return (pad + ext, slha.digest())The extend code takes as input the old digest, the plaintext length, and the data to extend as ext.

In the first 3 lines we are reconstructing the padding that was applied to the text before the old digest.

In the fourth line we create a new SLHA1 object.

In the sixth-seventh line we use library internals to recreate the internal state from the old digest and apply the length

Then we perform the update with new data and we return the newly appended data (pad + ext) and the new digest.

MD5

Some tools for generating MD5 collision (hashclash, fastcoll, SAPHIR-Livrables) or SingleBlock collision (very HOT).

Classical

Caesar cipher

Caesar KCA

On Caesar you can try a CiphertextOnly Attack (COA) aka Known Ciphertext Attack (KCA) by analizing the statistics of each character I’ve made a website that does this automatically by comparing the IC of each letter with ones from Italian and English dictionary.

This will only works if your alphabet is limited to: A-Z or a-z

An alternative can be xortool.

Caesar KPA

Also Caesar can be broken with a Known-plaintext attack (KPA).

If some messages are encrypted with the same key, you can recover the key from a Plaintext-Ciphertext pair and decrypt the other messages.

(or part of messages).

e.g. have the following ciphertext: dahhksknhzwoaynapodkqhznaiwejoaynap, we know that the crib (plaintext) starts with helloworld.

We can see that shifting by 4 return dahhksknhz, the starting ciphertext. So now we know that the key is shift by 4 and we can decrypt all the message. (Try it yourself ;)

Another demo is available here in this SECCON2016 challenge

Caesar CPA

In a Chosen-plaintext Attack (CPA) scenario, where you can input a plaintext in a Caesar encryption oracle, remember that shifting A by C will result in C, so a plaintext made of A’s will expose the Key as ciphertext.

This also works as a Chosen-ciphertext Attack (CCA)

Like in this HackThatKiwi2015 CTF challenge

Vigenere cipher

Vigenere is done by repeating Caesar for each letter in the plaintext with a different shift according to the key.

You can try a COA once you have guessed the keylength (with Kasisky).

Or You can try a KPA or CPA/CCA like in Caesar.

Also sometimes you will need to bruteforce a partial key like in this SECCON2016 challenge

Symmetric

XOR

See Caesar/Vigenere section

The XOR (symbol ⊕) is based on the Exclusive disjunction. (returns 1 only if inputs are different)

So note this rules:

A ⊕ 0 = A

A ⊕ A = 0

(A ⊕ B) ⊕ A = B

XORing a Plaintext with a Key will output a Ciphertext that XORed again with the Plaintext will return the Key.

SBox-Based Block Cipher

Block cipher Analysis example SharifCTF 7 - Blobfish

Feistel

A reverse-crypto SECCCON2016 challenge for Feistel

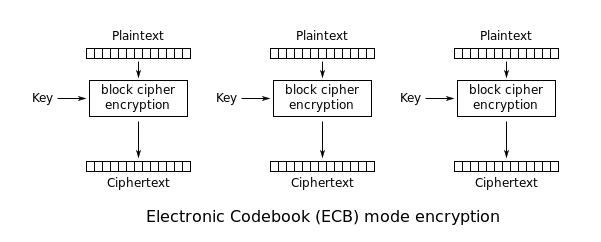

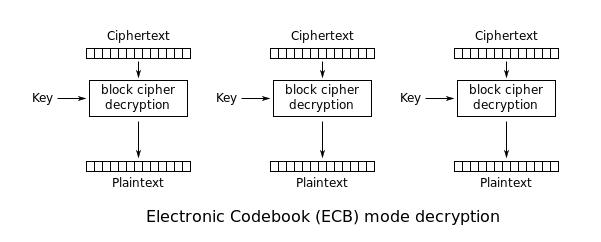

ECB Mode

ECB is the basic of block cipher mode. Every block of plaintext is encrypted with the same key.

This cause that identical plaintext blocks are encrypted into identical ciphertext blocks; thus, it does not hide data patterns well.

Replay Attack (Known Block Ciphertext)

Also if you know what Plaintext resulted in a certain Ciphertext, you can replay that Ciphertext or when you see that Ciphertext you know what was the Plaintext. (Only when the Key is constant!)

e.g. In this ABCTF2016 Challenge, you are given a bunch of AES-128 ECB Plaintext-Ciphertext pairs, and the encrypted flag e220eb994c8fc16388dbd60a969d4953f042fc0bce25dbef573cf522636a1ba3fafa1a7c21ff824a5824c5dc4a376e75

You can divide the encrypted flag into 16-byte blocks:

e220eb994c8fc16388dbd60a969d4953

f042fc0bce25dbef573cf522636a1ba3

fafa1a7c21ff824a5824c5dc4a376e75

And search each block individually in the Plaintext-Ciphertext pairs. This will give you the 16-byte corresponding plaintext.

Encryption Oracle Attack

Alternatively, if you have an Encryption oracle Attack available (that always use the same key) and the service append to your input a secret (secret suffix), you can go for a CPA.

You start by sending a message that is 1 byte shorted then the block length.

In this case the first character of the secret will fall in the first block,

Save the encrypted value of the first block, then send a new message like the first one but appending a random final byte.

You can then bruteforce the final byte.

When the encrypted value match the saved one, you have guessed the fisrt secret character.

e.g. Let’s use AES-128 ECB that has 16 byte blocks

We send the garbage message length 15 -> AAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

The server will reply with Enc('AAAAAAAAAAAAAAA'+secret) but the first block is equal to Enc('AAAAAAAAAAAAAAA'+secret[0]).

So now we can bruteforce the last character until the ciphertext match

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAa

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAb

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAc

...

This method will take max 256 attempt for the secret’s length, 4096 tries for a 16 byte blocks

There is a script that do this for the EncryptionService - ABCTF2016 challenge

CBC Mode

In CBC mode, each block of plaintext is XORed with the previous ciphertext block before being encrypted. This way, each ciphertext block depends on all plaintext blocks processed up to that point. To make each message unique, an initialization vector (IV) must be used in the first block.

Predictable IV Attack

In a CBC Encryption oracle, If you can predict the IV for the next message (or simply it’s a fixed IV) you can verify if a previous ciphertext comes from a guess plaintext.

You have a ciphertext block C1 and it’s IV IV1, you want know if that is the encryption of the plaintext P1.

If you can predict the next IV (IV2), you can made up your plaintext like: P2 = P1 ⊕ IV1 ⊕ IV2.

So you can send this new message to the server that encrypt it this way:

C2 = Enc(k,IV2 ⊕ P2) but with the forged P2 this become

C2 = Enc(k,IV2 ⊕ P1 ⊕ IV1 ⊕ IV2) = Enc(k,P1 ⊕ IV1).

C2 == C1 only if you have guessed P1.

IV Recovery

(aka. key used as the IV)

IV is not meant to be secret, because you can easily recover it.

If you have a ciphertext block, you can recover the key by letting someone decrypt C = C1 || Z || C1

(where Z is a block filled with null/0 bytes)

The decrypted blocks are the following

P1 = D(k, C1) ⊕ IV = D(k, C1) ⊕ k = P1

P2 = D(k, Z) ⊕ C1 = R

P3 = D(k, C1) ⊕ Z = D(k, C1) = P1 ⊕ IV

R is a random block that we can throw away.

Finally we can recover the IV with P1 ⊕ P2 = P1 ⊕ P1 ⊕ IV = IV

Bit Flipping attack

Note that if we XOR a ciphertext block, the next plaintext block will be XORed as well (X propagates like in the image).

If you have control over the plaintext P, you can fill a block P[i] with filler data Z that will be encrypted.

Once it’s encrypted you must find that ciphertext block C[i] and replace it with a XORed version of C[i], Z and your desired value G, like X = C[i] ⊕ Z ⊕ G.

When the server will decrypt the ciphertext, will get a different plaintext P’ where P’[i] will be indecipherable nonsense, but P’[i+1] will be your desided value G.

P’[i+1] = P[i+1] ⊕ X

= P[i+1] ⊕ Z ⊕ G

= Z ⊕ Z ⊕ G

= G

e.g. This scenario is common in website where cookies that are stored encrypted in the client and the server will decrypt them for every request.

You can select a very long username or password that will act as Z and set G to something like ;admin=true;. :wink:

Padding oracle attack

This vulnerability is possible because CBC is a malleable cipher (as seen in the bitflip attack).

If we make a small change in the ciphertext, when decrypted the resulting plaintext will have that same change.

This is not a strictly crypto vulnerability, but an implementation flaw.

The target is vulnerable if:

- Uses a flawed padding method (like PKCS#5, PKCS#7, or everything else… Developers, please use HMAC)

- The implementation leaks information about valid/invalid padding

If the implementation is vulnerable, upon decryption we should have 3 cases:

Case 1

Valid ciphertext - Implementation works correctly

The ciphertext decrypts to the plaintext tom that is a valid user.

Case 2

Invalid ciphertext - Error about invalid plaintext

The ciphertext decrypts to the plaintext aw89d that is an invalid user. Error reported for invalid user.

Case 3

Valid ciphertext with incorrect padding - Error about incorrect padding

The ciphertext decrypts to the plaintext sam that is a valid user but decryption fail as padding is incorrect.

The implementation leaks some information about this specific error.

We will assume PKCS#5 is used, so the final block of plaintext is padded with N bytes of value N.

If the block is full, append another block full of padding (N = blocksize).

Keep in mind the CBC decryption scheme.

P1 = D(C1) ⊕ IV

P2 = D(C2) ⊕ C1

The padding will be placed at the end of P2. If we bitflip the last byte in C1, the last byte in P2 will be flipped as well.

For convenience it’s better to work with the last 2-block of ciphertext, you can strip the previous one since we are working on recovering the last block backwards.

The objective is to recover D(C2), xoring it with C1 will give us P2.

Let Z be a block filled with null/0 bytes and || a byte concatenation function,

We start by submitting to the decryption-oracle (the decryption function) the input C

C = Z || C2

P'1 = D(Z) ⊕ IV

P'2 = D(C2) ⊕ Z

P'2 = D(C2)

For example

Z = 0x00000000

C2 = 0x4525535F

C = Z || C2 = 0x000000004525535F

P'2 = 0x0A72CE92

The implementation will decrypt this input, check the last byte of P'2 and report an invalid padding error.

We can try all the values from 0 to 255 as the last byte in Z.

The only input accepted without the padding error will be the value that decrypt to 0x01 (a padding of 1 byte).

Now that we have recovered the last byte of D(C2) and we can xor it with the last byte of C1 to get the last byte of P2.

We repeat this steps backwards for all the length of Z to retrive the full D(C2) and P2 next,

finally we can also repeat this process block-by-block to recover the full plaintext P.

I developed a python program and library to automatically perform Padding Oracle attack.

Alternatively you can use PadBuster.

This attack can easily be prevented by checks that the ciphertexts are valid before decrypting them, by using encrypt-then-MAC or AE/AEAD.

Asymmetric

RSA

Common Modulus

For common modulus attack see this writeup